Learn from the Exemplar

At a recent Teach UP session, I had the pleasure of observing two masterful educators and facilitators, Paul Powell and Jesse Corburn, guiding a room of future educators through techniques to ensure student engagement. As participants dove into their final practice round of the day, demonstrable skills they didn’t have at the start prominently displayed, I got to thinking: What exactly made Paul and Jesse’s session so effective? What should we all steal and replicate in our work with teachers – new, veteran, and everything in between – a question that is especially resonant as we all begin to plan for a successful launch to 24-25 via summer PD with our teaching teams.

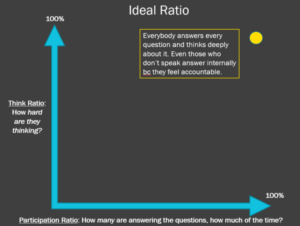

At a recent Teach UP session, I had the pleasure of observing two masterful educators and facilitators, Paul Powell and Jesse Corburn, guiding a room of future educators through techniques to ensure student engagement. As participants dove into their final practice round of the day, demonstrable skills they didn’t have at the start prominently displayed, I got to thinking: What exactly made Paul and Jesse’s session so effective? What should we all steal and replicate in our work with teachers – new, veteran, and everything in between – a question that is especially resonant as we all begin to plan for a successful launch to 24-25 via summer PD with our teaching teams.  Ratio refers to how deeply students are engaged with content, often measured via the cognitive demands of the material as well as one’s level of participation with the material. At its most basic, ratio is high and learning happens when all students actively engage with deep and meaningful content [graph at the right].

Ratio refers to how deeply students are engaged with content, often measured via the cognitive demands of the material as well as one’s level of participation with the material. At its most basic, ratio is high and learning happens when all students actively engage with deep and meaningful content [graph at the right].

It sounds simple, but it’s also not. Any experienced educator knows that you can’t just foist rich and nuanced content onto students who aren’t ready for it, as that creates cognitive overload that can result in disengagement at best and frustration at worst. The critical piece that unlocks learning is getting the ratio right: the right ratio to the right learner(s) at the right time. This is the true magic of teaching and learning, whether we’re working with students or adults.

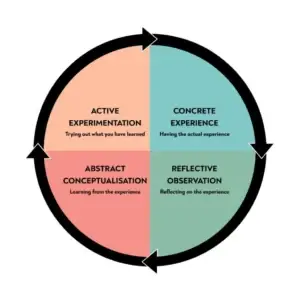

Researcher David Kolb shared important insight into ratio within the learning cycle in a 1984 published model of learning that still holds up today [image at right]: in his four-part sequence, learning starts with “concrete experience” – we all know that reading or hearing about something pales in comparison to being immersed in. Next, in “reflective observation,” you step back on that experience and attempt to make meaning of it. In “abstract conceptualization,” a learner comes to generalize or universalize their understanding, encoding it into long-term memory. And finally, the stickiest learning closes in a moment of “active experimentation” – or trying it out and practicing.

Researcher David Kolb shared important insight into ratio within the learning cycle in a 1984 published model of learning that still holds up today [image at right]: in his four-part sequence, learning starts with “concrete experience” – we all know that reading or hearing about something pales in comparison to being immersed in. Next, in “reflective observation,” you step back on that experience and attempt to make meaning of it. In “abstract conceptualization,” a learner comes to generalize or universalize their understanding, encoding it into long-term memory. And finally, the stickiest learning closes in a moment of “active experimentation” – or trying it out and practicing. See It,

First, Paul helps immerse participants in the vision for exemplary instruction through a video review of master teachers (e.g., concrete experience) – as seen in this clip.Name It

Next up, we see Jesse build on the initial learning that begins to develop through concrete experience and strengthen it through reflection and conceptualization. In this section, Jesse facilitates a powerful discussion, where participants really take on the learning load, and then offers the group shared principles and vocabulary to help them encode their takeaways from short-term memory into long-term knowledge. Jesse:

- Affirms strong ideas through non-verbal cues (head nods; open, excited facial expression) and brief language (“Yes!” “Great!”)

- Ensures a number of participants share responses before he adds his expertise

- Eventually provides a slide with shared concepts and technical language – which align with what has already been shared – to solidify and universalize the takeaways in the room

Do It

With these initial learning components in place, participants are ready for the greatest ratio push of the session: practice. Let’s watch how Paul and Jesse execute this period of active experimentation in two parts.First, they allow participants to “prepare for practice.” Jesse sets this up beautifully: he puts this micro classroom culture technique they’ll practice back into context (“How do we do [non-verbally correct student behavior] while teaching a lesson and not breaking our flow of instruction?”); without this, practice time could feel it lacks purpose and connection to the overall goal of actually teaching students content. Next, Paul builds momentum and excitement for the practice itself with the line, “So buckle up!” Though easy to miss, this is such a powerful addition, as practice can feel intimidating and awkward, yet this builds in a small moment of joy that catalyzes participant engagement. Finally, Paul reviews the directions and offers a quick model as one last example before teachers are given time for independent preparation.