By Paul Powell and Kathryn Perkins

A few months back, we wrote about the value of regular, systematic retrieval practice in the math classroom. The headline: retrieval is essential for learning. Without repeated, spaced at bats with interleaved information that lead to the sweet spot of “desirable difficulty,” there is no transfer from working to long-term memory, and therefore, no learning.

While the power of retrieval to encode new information is already well known, a new study piqued our interest this week as it offered a new – and powerful – benefit of retrieval practice. In “Effects of retrieval practice on retention and application of complex educational concepts,” Daniel Corral and Shana Carpenter studied how retrieval impacts not just memorization, but the ability to apply learned information to new situations (“transfer”). They found that retrieval benefits both.

Carl Hendrick summed it up beautifully:

The key finding was that three rounds of retrieval practice produced significantly better performance than restudy and quiz study on both repeated questions (testing the same material) and application questions (requiring learners to apply concepts to novel scenarios) when tested one week later. Importantly, this transfer advantage persisted even when controlling for memory accuracy, suggesting retrieval enhances learners’ ability to recognise when a concept is relevant in a new context, not just their memory for the concept itself.

Given its heightened importance, we thought we’d spend this month refreshing our most recent blog on retrieval, which includes a great clip of retrieval in action.

Designing Retrieval Practice

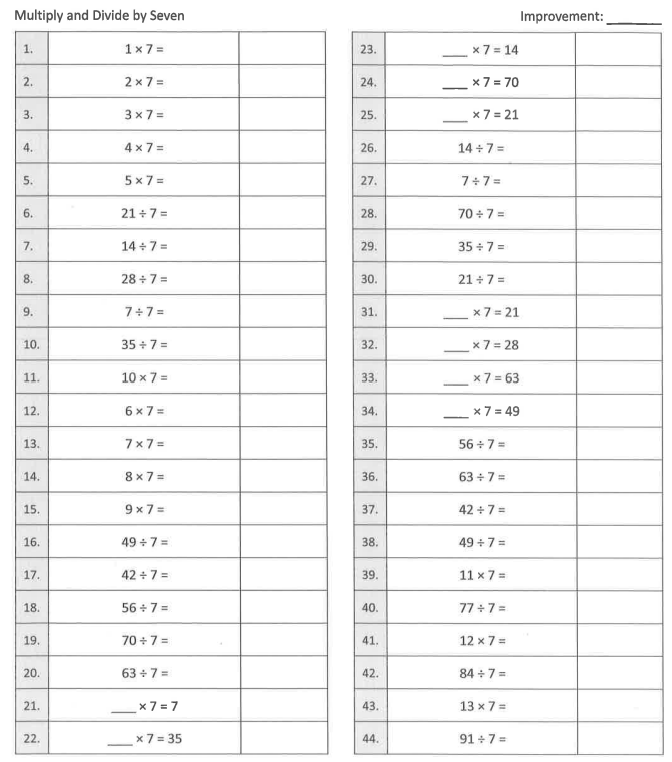

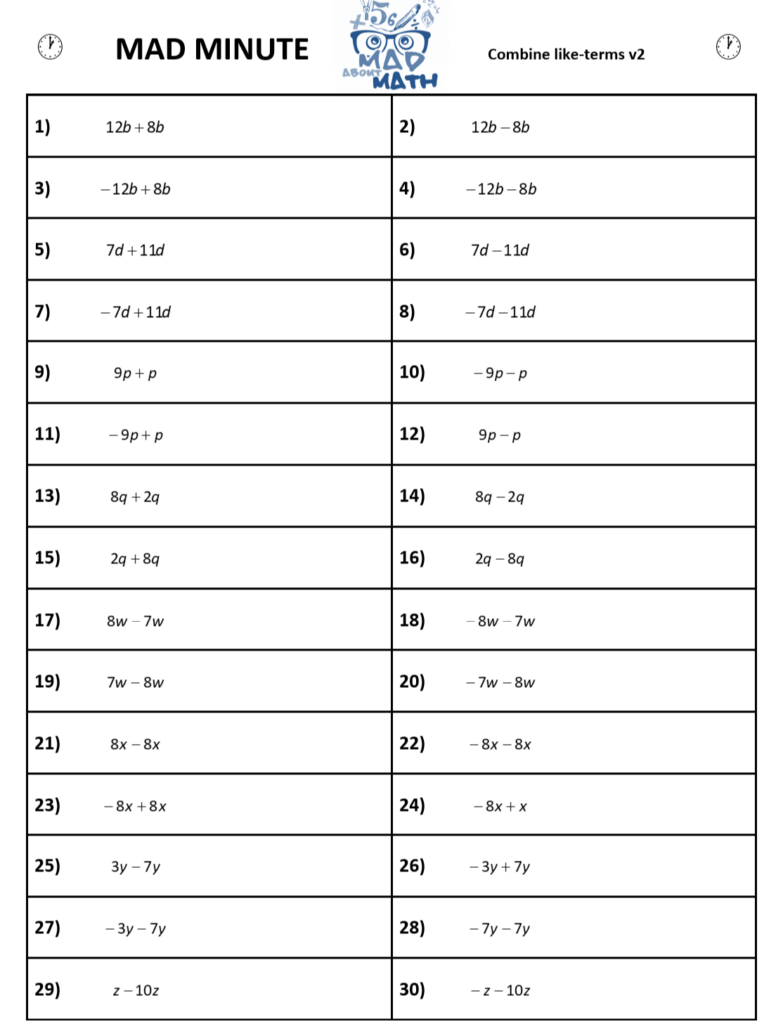

If the content (rather than delivery) is more your focus, we also wanted to offer some new examples of high-impact retrieval practice. Below, we’ll offer two samples – one from 3rd-grade math and one from Algebra 1 (they’re also here if you’d like to return to them later). Try out one or both, completing it as a student would while reflecting as an educator:

- What stands out to you about the structure of the practice or the process of completing it?

- How do the practice sets achieve desirable difficulty?

What did you notice? Maybe you pulled out the repeated practice and skill interleaving (in 3rd grade: multiplication and division – plus the skill of determining how to handle an unknown in different places). As the student, we also hope you felt the practices hit desirable difficulty, offering the gentle pressure of cognitive load throughout: while similar, the problems weren’t similar enough to put you on autopilot, which we know slows learning. (In fact, research shows that the most impactful fluency practice falls in the 70-80% mastery window.) Maybe you thought to yourself that practice like this would only take a few minutes each day – crucial, since we know how valuable classroom time is.

Pitfalls to Avoid

While regular retrieval offers undeniable value add to instruction, there are key pitfalls to avoid – namely:

- Seemingly endless problem sets: The best retrieval happens daily – but in short bursts. Think 2-5 minutes total, with its corresponding number of problems.

- Problem sets that offer little variation: If students repeat essentially the same problem over and over, they go on autopilot, and the result is practice that is too easy. Remember: interleaving skills supports hitting the desirable difficulty that leads to most efficient learning.

- Not offering feedback: Retrieval is only effective if students get immediate feedback on their work. This doesn’t have to be time intensive or lengthy: at a minimum, share answers aloud and have students correct their papers; ideally, leave time for a quick review of 1-2 challenging problems – even if this just means stating a response and a 1-sentence explanation.

- Compromising new material: If we aren’t disciplined, retrieval practice can take more time than we initially allotted, thereby compromising the introduction of new material. A quick fix here is to set a timer and stick to it. You might even engage students in a time challenge – though remember, too, that it’s important to keep retrieval low stakes.

We hope you’re inspired to try it out, and maybe even commit to a regular retrieval cycle in your classroom in 2026. Wishing you a wonderful holiday and a happy New Year until we see you back in January.