By: Paul Powell and Kathryn Perkins

Earlier this month, we hosted a new workshop for our team titled “The Science of Math.” This represents an area of increasing importance, not just close to home here in Florida. Nationally, the most recent NAEP assessment, considered “our nation’s report card, showed alarming trends in math, including a continued lack of post-COVID recovery (though the downward trend began well before) and the greatest declines for students already performing in the bottom quartile. As written earlier this year: “The country’s lowest-scoring students are in free fall.”

As such, we’ve been thinking a lot about math lately, pondering the questions: What does cognitive science tell us about learning math? And how can we make these takeaways applicable and actionable at the school and classroom level?

In an earlier blog on the topic, we focused on the power of retrieval practice; this month, we’ll shift to introducing new material effectively.

Explore or Explicit?

Researchers have often posed the question of whether to introduce new material via student exploration or direct instruction, and the research is confusing, with multiple studies in each camp citing positive effects of the approach.

The Research

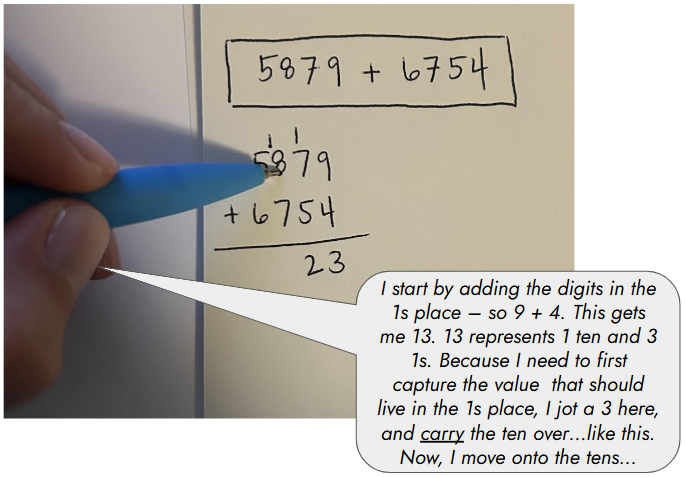

While both approaches can add value pending context, at FCI, we put a stake in the ground that worked examples, an example of direct instruction, are often part of the best introductions to new material. A worked example refers to a step-by-step illustration of problem solving, completed live with students. Once complete, it offers a lasting record of the thinking needed for success with similar problems in the future (see image at right).

The benefits of direct instruction are well-documented, with one of the strongest research bases of all teaching practices. Moreover, it has been shown to be most important for students struggling with content, which means it represents one of the possible solutions to our nation’s current “bottom falling out” trend. Within the world of direct instruction, worked examples show real impact. In the only meta-study on the subject, conducted by esteemed researcher John Hattie, worked examples were demonstrated to have an effect size of 0.48 – crossing the 0.4 “hingepoint” for high-impact teaching practices.

Leveraging the Worked Example

We’re excited to share a clip of a powerful worked example in action – by taking you where we haven’t yet ventured in this blog: into the world of calculus! (And before you stop reading, give this a shot! We promise you don’t have to be a calc expert – or even calc comfortable – to glean best practice from the clip.)

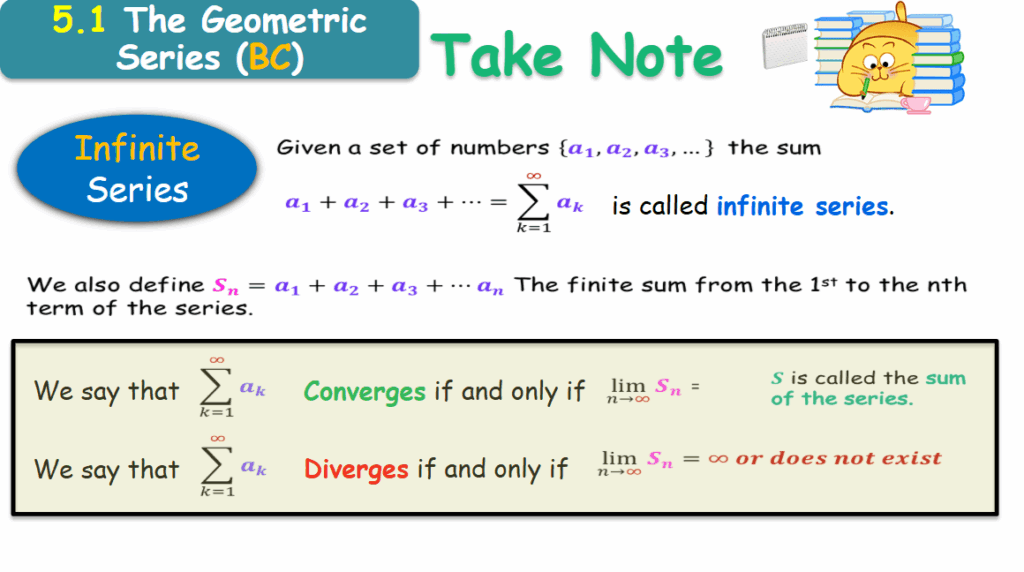

A little context: Jose Cobo, a high school calculus teacher at True North Classical Academy, is about to roll out a new topic, convergent geometric series, with his students. High level, if you add an infinite set of consecutive numbers, as described by a series, and the sum approaches a number (rather than infinity), we say that the series converges. (See below for the notes that Mr. Cobo shared with students for more on the mathematical concepts and notation, if of interest.)

As you watch this clip, consider how Mr. Cobo leads the worked example to introduce this concept. What is its general structure? When does Mr. Cobo choose to engage the students in the example by asking questions, and when does he decide to think aloud the content himself? Let’s take a look.

You may have noticed how Mr. Cobo thinks aloud when introducing new process and concepts to his students:

- Process: naming “what” and “how” (e.g., “Let’s get some of the values. When k=1…” or “Look at this trend. S1 is __, S2 is __…”)

- Concepts: naming the “why” behind a particular move (e.g., each number in a series represents the sum of all the previous numbers: “S2 represents the sum of the first two values in the sequence, so we can plug in ½ + ⅙ here.”)

You likely also noticed that Mr. Cobo kept students engaged in the activity via quick questions when they were already fluent in the content. Examples included both basic fact fluency (“What is ¾ + 1/20?”) as well as vocabulary (“What do we call this?” [partial sum]).

Complex content but simple teaching. And transferable to any math – or any content, for that matter. We hope you’ll try it out the next time you’re introducing new material. Let us know how it goes!