Here at FCI, we’ve been thinking about the power of background knowledge to drive student learning for much of this fall. It all started with a visit from esteemed cognitive scientist and University of Virginia professor Daniel Willingham at a convening of our distinguished school leader Fellowship – and suddenly, it felt like every school visit we went on, article we read, or podcast we listened to offered yet another compelling example in favor of a knowledge-rich instructional experience for students.

Here at FCI, we’ve been thinking about the power of background knowledge to drive student learning for much of this fall. It all started with a visit from esteemed cognitive scientist and University of Virginia professor Daniel Willingham at a convening of our distinguished school leader Fellowship – and suddenly, it felt like every school visit we went on, article we read, or podcast we listened to offered yet another compelling example in favor of a knowledge-rich instructional experience for students.

In today’s blog, we’ll offer a quick look at research on the impact of background knowledge on student achievement and offer one practical application for your classrooms. In the coming months, we’ll add more tips for implementation – and before long, we’re confident you’ll experience the power of knowledge to accelerate learning as these Velcro webs take hold in your students’ minds!

Background Knowledge: The Research

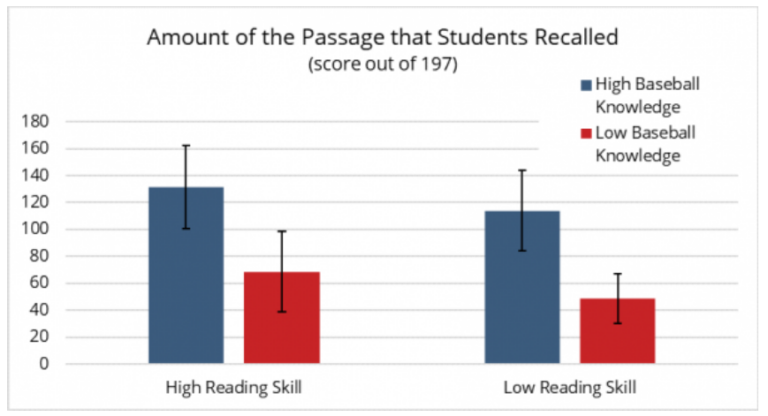

In the late 1980s, researchers Donna Recht and Lauren Leslie ran a study on reading comprehension that has been so widely discussed in the years since that it is now known in ed circles as simply “the baseball study.” In the study, students were grouped into one of four categories – those with high reading achievement who were high or low in baseball knowledge and those with low reading achievement who were high or low in baseball knowledge – and then assessed on their understanding of a story about baseball. Unsurprisingly, students with previously high reading achievement and high levels of background knowledge performed best on the new reading passage. Where things got interesting, though, is that students who were historically lower performing but had high knowledge of baseball outperformed those who had high reading achievement and low levels of baseball knowledge. (See image, courtesy of Marc Seidenberg’s blog.) In other words, background knowledge about the topic of the text was more important to reading comprehension than was previous reading achievement.

Fast forward to David Grissmer and team’s 2023 study of nine Colorado charter schools implementing knowledge-rich curricula and its impact on student outcomes. For the eight middle-to-wealthy schools in the study, the effect size of the knowledge-rich curricula was 0.445 for English, a value widely considered to achieve the threshold of significance in research circles – comparable to practices like ongoing formative assessment or small group instruction in a classroom. For the low-income school in the study, though, the effect size was a massive 1.299 for English and 0.997 for math – so large as to eliminate the achievement gap in all subjects. While a small sample size, these results are overwhelming and, if replicated, would place knowledge-rich instruction at the very top of instructional strategies by effect size.

Experience it Yourself

Before moving into application, we’ll offer one final example so you can feel the effects of background knowledge at work on your own cognition. This one comes from Dan Willingham’s Why Don’t Students Like School? (which we highly recommend for further reading, along with Natalie Wexler’s The Knowledge Gap, for those interested).

Here’s the activity. Read the following list of letters once, then cover it up and see how many you can remember.

XCN

NPH

DLO

LGM

TFA

QX

Take note of your number, and then repeat with the list below:

X

CNN

PHD

LOL

GMT

FAQ

QX

How many this time? We bet many more. If you performed similarly to the average, you got around seven unique letters from the first list and close to all in the second.

Now, take a closer look at these lists again. You might notice they are actually identical, with only a small difference in spacing that organizes the letters differently.

So why do we perform so differently across the two lists? It seems obvious: the units of letters in the second list each represent something meaningful, making them much easier to commit to memory. To tie it to background knowledge: when we already have associations, information – knowledge – about anything, we learn quicker and with greater ease.

Implementation

If you, like us, are compelled by these examples and research, over each of the next few months, we’ll bring you a new strategy for building and activating student knowledge to drive learning outcomes. And while some ideas may loom large (e.g., overhauling curriculum to build an intentional knowledge base across contents and grade spans), others can be tackled as soon as tomorrow’s first-period class.

Lesson Launch to Build “Just in Time” Background Knowledge

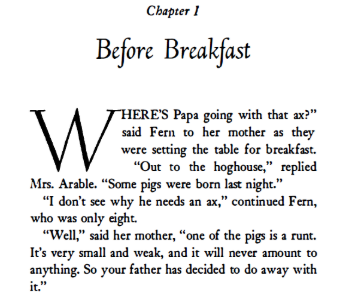

For many, the beginning of a lesson is an easy and impactful time to build or activate student background knowledge before introducing new material. Let’s follow an example of what this might look like with a well-known elementary literacy text: E.B. White’s Charlotte’s Web. Imagine you are about to read Chapter 1 with students, which begins like this:

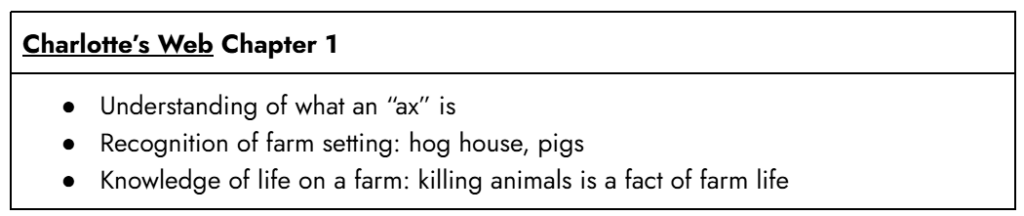

If you ask yourself,” What background knowledge do students need to effectively engage with today’s lesson?” you might come up with something like the list below:

If you ask yourself,” What background knowledge do students need to effectively engage with today’s lesson?” you might come up with something like the list below:

Without these elements of knowledge, it’s unlikely students will be able to decipher even the basic action of these paragraphs: Fern’s father is planning to kill a pig.

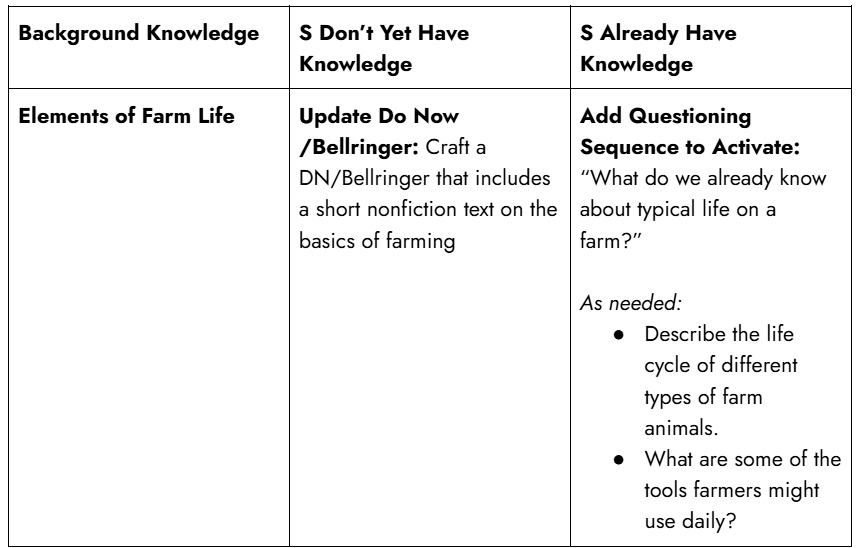

Once you’ve anticipated the needed background knowledge, determine whether students already have this (from previous content in your class and/or another class/grade level) or whether you’ll need to introduce the knowledge. If students have already had exposure to it – as will be the case much of the time – a questioning sequence at the lesson’s beginning often is sufficient, while introducing new knowledge may require an updated bellringer activity or teacher model. Here are a few options using our Charlotte’s Web example:

If you’re a leader, consider how this pre-thinking could fit into your team’s “prepare-to-teach” process, and then plan to roll out. You could have a few veteran teachers trial in their classrooms or coach your instructional leadership team first, hold a department meeting on what this looks like within each content, or offer broader professional learning to your entire staff. There’s an option for every school.

These simple steps will activate the rich web of knowledge students already have, allowing them to add new knowledge and deepen their analysis of content immediately. We’re excited to hear how it goes!