I recently enjoyed sitting in a 3rd-grade literacy class midway through E.B. White’s classic, Charlotte’s Web. As the teacher facilitated a beautiful shared reading of a new chapter, students encountered the following exchange between Charlotte and a fellow animal:

- “Does anybody here know how to spell terrific?”

- “I think,” said the gander, “it’s tee double ee double rr double rr double eye double ff double eye double see see see see see.”

- “What kind of acrobat do you think I am?” said Charlotte in disgust. “I would have to have St. Vitus’s Dance to weave a word like that into my web.”

The teacher smartly paused, realizing the difficulty of the section, and asked if any students knew what “acrobat” meant. How should the teacher address this challenge, which comes up daily in all content areas and grade levels?

Read on for a quick look at the research and its practical application in the classroom.

The Why: Research on Vocabulary

The science of reading has long considered vocabulary instruction a key pillar of learning to read. After all, in addition to being able to sound out words, students have to know the meaning of the word to comprehend the text. This is related to the research, covered in last month’s blog, which shows that a vast and varied knowledge base helps us learn more quickly and adeptly because knowledge acts as velcro to other knowledge. In the case of vocabulary, more words = more velcro.

In addition to supporting comprehension generally, knowing many and varied vocabulary words reduces the load on our working memories at any given moment. Cognitive science has shown time and again that we can only keep so much information in our brain’s active (“working”) portion before we overwhelm it. The more words we know, the lower the demand on our working memory, leaving space and capacity for deeper analytical thinking.

Everywhere you look, the research tells us that the direct and explicit building of student vocabulary is key to deepening learning.

The How: Keys to Vocabulary Instruction

While leveraging context clues is not a bad strategy in times of need, it doesn’t always (and we’d argue doesn’t often) offer students what they need to decipher precise and nuanced word meanings. Thus, words should be taught explicitly, which happens when teachers provide students with a high-quality definition, share word use in multiple contexts, and offer repeated opportunities for practice.

Let’s take our “acrobat” example through this cycle.

Explicit Vocabulary Instruction

When the class encounters an unknown word, the teacher begins by offering a high-quality definition:

- “Class, we just saw a word that’s likely new to most of us: acrobat. Say ‘acrobat.’ [students repeat] An acrobat is ‘someone who performs difficult physical feats, often as entertainment.’” [teacher jots this down as students copy]

Then begins the series of word use in context – perhaps something like:

- “Why would it take an acrobat to weave the word ‘terrific’ into Charlotte’s web, especially as the goose spelled it? Turn and talk!”

- “Raise your hand if you’ve seen an acrobat in action. Who can describe what they saw?” [teacher calls two students]

- “Think back to the short story we read last week. In what moment would Bradley have had to move acrobatically? Jot it down in the margin of your paper….and now, turn and discuss!” [teacher monitors the stop and jots and turn and talks before calling on one to two students]

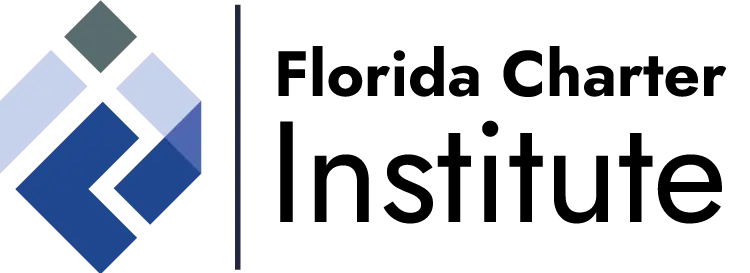

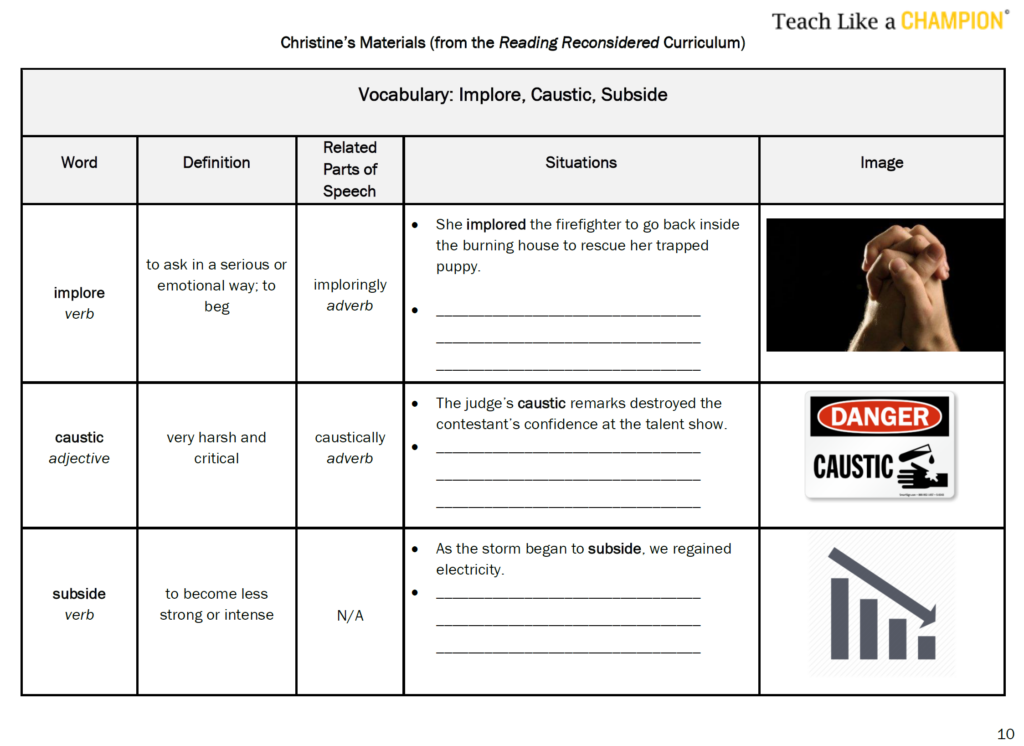

Most days, teaching one to two words this way makes sense, spending no more than 3-5 minutes on each. However, we should occasionally pre-teach a small set of words that students will need for success in an upcoming reading, lesson, or unit, following the same sequence of high-quality definitions, multiple contexts, and repeated practice. See below for an example of this from our friends at Teach Like a Champion:

Following their explicit instruction, vocabulary words should be spiraled in the short term: on a homework assignment, in a Do Now activity, or by connecting to a new vocabulary word being explicitly taught in a future lesson. Periodic retrieval practice, such as low or medium-stakes quizzes, that are short, predictable, and regularly executed, also prevents forgetting. All in, Beck and McKeown’s research in Bringing Words to Life suggests that students need ten touches with a new word in various contexts to begin to use the word effectively.

So try it out in your classrooms and with the teachers you coach! By flipping the script and treating vocabulary instruction not as a skill but as knowledge, you’ll build your students’ cognitive capacity not just today, but over the long term.